A Star is Born

November 15, 2021

From the Nov/Dec 2021 issue of

Sactown Magazine.

by Leilani Marie Labong

Nearly 15 years in the making, the SMUD Museum of Science and Curiosity is ready to open a portal to both the past and the future on the banks of the Sacramento River, pairing a historic 1912 power station with Northern California’s most advanced planetarium.

Its mission: Reinvigorate the waterfront, position our region as a tech and health sciences powerhouse, and ultimately inspire generations of kids from all walks of life to dig deeper, reach further, dream bigger and discover for themselves that the sky’s the limit.

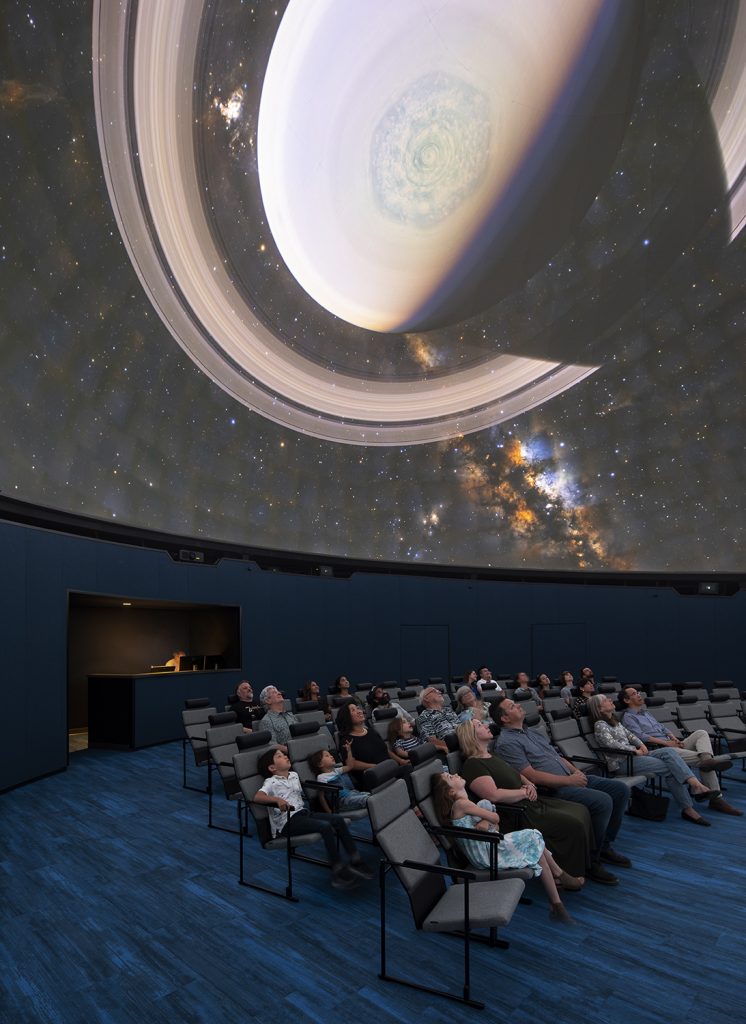

Under the myriad galaxies twinkling above my head in the planetarium at the new SMUD Museum of Science and Curiosity (MOSAC), opening to the public on Nov. 13, a voice shooting through the dark takes aim at whatever part of me still harbors school-age anxiety over being asked a question I don’t know the answer to.

“Can you point out the Big Dipper?” asks Harry Laswell, the museum’s former executive director and current board member.

I’m pretty sure that I can’t, but I crane my neck in various directions anyway to gain a more sweeping perspective and whip my eyeballs around the dome—at 46 feet in diameter and 35 feet from floor to apex, this is no easy feat—to find this ladle-like constellation that appeared to Africans as a drinking gourd, to the Irish as a plough, and to some American Indians as a bear pursued by three hunters. But for a galactic novice such as myself, a lifelong urbanite whose night-sky views have been historically dimmed by city lights, finding this specific sequence of eight stars is proving futile, even with the latest space imagery transmitting from NASA’s cloud system and emblazoning this massive dome screen through six high-resolution projectors.

“It’s the most technically sophisticated planetarium built in Northern California so far,” says Laswell. A stratospheric improvement, if you will, upon the much smaller Tot Planetarium at the former Powerhouse Science Center (née the Discovery Museum Science & Space Center) just outside Arden-Arcade—a 10,000-square-foot “mom-and-pop science center” in his words—which relied on a clunky star projector to beam preprogrammed images of celestial objects onto its dome.

“A second-grader would be able to locate the Big Dipper better than me,” I sheepishly admit. Pupils aplenty will certainly have the chance. As a launching pad for hands-on learning in science, technology, engineering, art and math (in recent years, a more broad-based STEAM education has gained traction on its STEM antecedent), the 50,000-square-foot MOSAC campus expects to welcome approximately 60,000 school children from 17 counties in its first year.

This aerial rendering shows MOSAC’s campus, which civic leaders hope will be a catalyst for more riverfront development. (Rendering courtesy of Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture)

“Let’s go to Saturn!” Laswell says, unfazed by my failure to identify the night sky’s marquee constellation. Before I know it, we are approaching the vaporous planet, located over 800 million miles from our big blue marble, as if we are in a spacecraft traveling at an unknown multiple of warp speed, dodging the infinite particles of rock and ice—some as small as a grain of sand, others a full kilometer in girth—that make up the celestial body’s characteristic rings. While my brain knows that I’m securely fastened to Earth in one of the planetarium’s 120 seats (butt in chair, check; feet on floor, check), my body actually feels like it’s floating, as if I were really cruising the cosmos. Vicarious space travel has its life-sustaining privileges, namely gravity and oxygen.

From the blurry perspective of a car-bound earthling traveling along Interstate 5 between the I Street Bridge and the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers, the new planetarium is partly distinctive for its exterior surface of zinc tiles, already gaining a splotchy patina that may eventually—or may not ever, depending on your artistic eye—resemble a telescopic view of the moon. But while this hard-wearing outer metallic layer weatherproofs the dome’s dense, sound-insulating strata of gypsum, plaster and rebar (pro tip: upon request, the mathematical beauty of the skeletal structure can be viewed inside the theater using special lighting), its future expression as the surface of a lunar body has little bearing on the already well-established symbolism of the sphere in architecture.

For instance, the 180-foot-tall, aluminum-clad orb that anchors Walt Disney World’s Epcot theme park manages to convey a kind of timeless high-techery despite its 1982 design. The Biosphère in Montreal, a transparent geodesic structure fashioned from interlocked steel tetrahedrons for the 1967 World’s Fair Expo, was American architect R. Buckminster Fuller’s symbol of societal innovation. And as conservatories for more than 40,000 rainforest plants from all over the world, the three glass Amazon Spheres in downtown Seattle function as a lush biodome utopia for the workforce of the tech giant’s headquarters.

As a wordless wayfinder for MOSAC, the dome stands out even more in relation to the two other notably flat-roofed rectilinear buildings on the River District campus—a new polygonal science building, where the planetarium is located, and the old PG&E River Station B. The latter, an elegant Beaux Arts-style former electrical substation from 1912, provides classical gravitas to the project through its sublime symmetry and regal arched elements. Designed by renowned San Francisco architect Willis Polk, the concrete building is on the National Register of Historic Places and an extraordinary example of adaptive reuse (more on this later) rife with metaphorical intent (also forthcoming). But most of MOSAC’s architectural futurism is contained within that shiny ball.

The new planetarium will be the most technically sophisticated in Northern California. (Photo by Kyle Jeffers)

“Typically a sphere screams science,” says Jason A. Silva, principal architect at Dreyfuss + Blackford Architecture, who has been working on the new science center since drafting its earliest blueprints in 2007. “If you didn’t have the dome, you might say, ‘Is that an office complex?’ or ‘Maybe it’s a water testing facility?’ ”

The science center’s previous design iterations featured the dome encased—like a rare giant pearl—inside a glass box, but with solid walls on some sides that obscured the view of the dome from certain angles. Ultimately, the dome was liberated from its structural encasement for all to see.

“Now the science center is instantly iconic and makes clear that Sacramento wants to attract more science industries, more healthcare jobs and more tech-sector employers,” says Mayor Darrell Steinberg over a late-afternoon Zoom in mid-August. “And I know it’s going to be a catalyst for even more development on the waterfront.”

MOSAC’s current executive director Michele Wong, co-owner and former CEO of the Gold River software company Synergex, cosigns the mayor’s optimistic forecast, but as a longtime tech CEO, also sees the center’s role in leveling the playing field. “We always struggled with hiring engineers in general,” says Wong of her time at Synergex. “But one thing that was always clear is that there just definitely were not ever many women in the field. So one of our missions here is to make sure that we are reaching all students.” One way that MOSAC engages students is through its weeklong Camp Curiosity summer program: “We’re making sure that we’re getting to the schools that wouldn’t otherwise be able to have this sort of experience.” MOSAC is working to develop a scholarship fund to cover the cost of the camps for the students who can’t afford them.

“Just seeing all the kids and seeing how excited they are; that is the high point for me,” says Wong. That and seeing the new building complete after a nearly 15-year journey. “I still get goose bumps when I walk through.”

Among the gleaming new facilities energizing the region are the LEED Platinum Golden 1 Center and the SAFE Credit Union Performing Arts Center (formerly the Sacramento Community Center Theater), a newly renovated Broadway-class auditorium. In addition, Capital Public Radio’s new glass-fronted downtown HQ—complete with a 200-seat performance space—is on track to open next spring. But as far as Laswell is concerned, the River City metro area has been “relatively under-museum-ed.”

He means no offense, of course, to Sacramento’s iconic cultural institutions of the sort, including the Crocker Art Museum, the oldest public museum west of the Mississippi; the California State Railroad Museum, where train buffs pilgrimage to see its 21 immaculately restored heritage locomotives; the Sacramento History Museum, with its viral TikTok star, octogenarian docent Howard Hatch; and even the quirky Museum of Medical History.

At the very least, the new science center might be just the catalyst we need to usher in a more vibrant waterfront. Because if the prevailing astral theory is correct, even the universe and its infinite potential emerged from the tiniest spark.

✦ ✦ ✦

The beautiful projection of California waterways that will be transposed from the ceiling onto a horizontal topographical map in MOSAC’s Water Challenge exhibit features the alpine lakes, iconic torrents and slithering tributaries that many of us have waded into, skipped rocks across or even floated a canoe upon. Reaching into the beamed-down map scene is encouraged, and in doing so, images of these aqueous bodies engulf, curve or swirl around faces and fingers, a way to soak in the features of our watershed—increasingly periled in the fast-moving era of climate change—without actually getting wet.

“There couldn’t be a more timely exhibit than Water Challenge,” says Steve Wiersema, principal of Oakland-based West Office, which designs museum exhibits. “A few years ago, , water seemed like less of an issue. But now it’s a huge issue.” Other elements of the presentation meant to stir dialogue about conservation include a virtual kayak trip around three wetlands, a swim lesson from fish headed upstream, and even meal planning to demonstrate how much water it takes to grow food.

A reproduction of an Apollo-era NASA spacesuit in the Destination Space exhibit. (Photo by Raoul Ortega)

In an around-the-river-bend kind of way, the exhibit also tributes the significance of water to the new MOSAC campus. After all, the exhibition hall inhabits the magnificent volume (think 55-foot-high ceilings and 22,000 square feet of space) of the restored 1912 PG&E River Station B, once the largest electrical steam station in Northern California. By pumping water from the adjacent Sacramento River through its four turbines, electricity was generated for the surrounding area.

“At the time, electricity was high tech, it was the newest thing,” says architect Jason A. Silva. “It was connecting the community in more ways than one.” Connectivity thematically prevails throughout the design, but as a model of adaptive reuse (that is, the process of giving an old site modern purpose through an immaculate restoration), River Station B is symbolically the project’s most significant bridge, in this case, to the past. Another of Willis Polk’s turn-of-the-century PG&E substations gained a second life in 2008 as the new home of the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, transformed by New York-based architect Daniel Libeskind, who viewed the building’s high-voltage past as a source of emblematic energy for the modern-day institution.

After PG&E shuttered River Station B in 1950, it changed ownership several times, eventually landing on the city’s books in 2000. Dreyfuss + Blackford had completed several doomed designs for the property, including a railroad technology museum and the would-be headquarters for the Department of Water Resources, a “Water Palace” complete with manicured grounds and large reflecting pool, which seemed to give the building, once surging with electricity, the gravity of a mausoleum.

Despite these big plans, the neglected building continued to sink deeper into disrepair, a decaying shadow of its former self—a product of the City Beautiful Movement, which called for constructing monuments and structures of Beaux-Arts grandeur to beautify American metropolises during the turn of the 20th century. (Also built during this pivotal urban planning campaign was Polk’s other Sacramento design, downtown’s historic D.O. Mills Bank building from 1912, currently home to The Bank food hall.)

Destination Space includes models of conceptual habitats on Mars and the moon. (Photo by Raoul Ortega)

In 2005, Dr. Evangeline Higginbotham, then the executive director of the Discovery Museum Science & Space Center, saw past River Station B’s deteriorating concrete walls and caving-in roof, envisioning instead a grand science center worthy of the capital of California. Even though the Discovery Museum, with roots extending to 1951, had long preceded the Exploratorium in San Francisco, founded in 1969 by physicist Frank Oppenheimer of Manhattan Project fame, its small-town charm was no match for big city cachet.

One can only assume that the Exploratorium’s breathtaking original location in view of the Golden Gate Bridge, at the Palace of Fine Arts (also a Beaux-Arts marvel—that towering colonnade, that majestic rotunda!—designed by Berkeley architect Bernard Maybeck for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition) had something to do with its success. Today, more than 300 science and space centers around the country have been molded in the spirit of the Exploratorium (which relocated to two historic buildings on Pier 15 in 2013), including places Silva visited in the name of research, like the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in Portland, the San Jose Tech Museum and Oakland’s Chabot Space & Science Center.

To boost the Discovery Museum’s signal to the level of its peers, Higginbotham wrangled a couple of cohorts—real-estate developer and museum volunteer Johan Otto and Michele Wong, then a board member—to help her draft a development proposal to the city for River Station B. Their bid finished second to someone else’s housing plan. “These housing people came in with this very fancy rendering of luxury condos where MOSAC’s parking lot is now. But they had no idea what to do with the PG&E building,” says Otto, president of Carson Development and former head of the now-defunct Sacramento Trust for Historic Preservation. “They were just ignoring it. And that cracks me up.” In due time, the Great Recession would arrive to pound a ruinous kibosh on the housing market anyway, so once again the scenic parcel would be up for grabs. Higginbotham passed away in 2009 from cancer, but not before the science center project was officially underway at the waterfront location of her choice, in the grandiose building of her dreams. The rest is MOSAC history, albeit lengthy and meandering, perhaps as the river intended.

✦ ✦ ✦

An acrylic portal in the Nature Detectives gallery, also designed by West Office, is destined to be a kind of superhighway for drones—not of the meddling, unmanned aircraft variety, but rather of the honeybee sort. Soon they’ll buzz through the tunnel from their live indoor hive and into a rosy canopy of more than 200 Pink Flair and Yoshino blossoming cherry trees. The forthcoming Hanami Line at Robert T. Matsui Park, which skirts the MOSAC campus, is projected to begin construction in spring 2022, much to the delight of these hard-working nectar collectors and the blushing sweethearts who will set foot on the riverside trail, inspired by the seasonal, centuries-old Japanese tradition of admiring cherry blossoms, and brought to life by the Sacramento Tree Foundation.

Not dissimilarly, the old River Station B is connected to the new science building, where the planetarium is located, via the architectural equivalent of a bee tunnel or, going by Silva’s more mechanical comparison, a structural “gasket”—in this case, double-height in size with a façade in can’t-miss-it red. While the connector’s large banks of windows symbolize the importance of transparency in science and technology (calling Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos to the witness stand), they also serve to light up the lobby in the day without much need for actual wattage and glow the building like a lantern at night, when adults will roam for after-dark events or a gamut of private to-dos, including string concerts in the acoustically sound planetarium (stars overhead optional) and even weddings (two have already been booked).

Silva and I are standing on the mezzanine level of this red node, above a rambunctious fray: In the ticket lobby below, high-decibel recreation is in full effect for kids taking part in Camp Curiosity. MOSAC hosted a summer’s worth of these week-long science programs for kindergarten to sixth-grade students in topics ranging from an exploration of alternative energy sources called “Earth’s SuperPowers” to a maker lab titled “Dream It. Build It,” which challenged the tinkering inclined to match a familiar goal: “We dreamed of building a museum. What do you dream of building?”

The west-facing façade of the historic River Station B has been restored to its original 1912 glory. (Photo by Kyle Jeffers)

From our high perch, the architect casually points through the windows, in the direction of River Station B. At first, this modest partial view of the rehabbed edifice’s east face, the original backside of the building, didn’t catch my eye—after all, it’s only a corner that merely hints at the restoration’s magnitude, from the preserved concrete walls to the reconstructed cast-stone cartouche, which crowns the colossal, reimagined front doors, now metal instead of wood. In fact, most of this architectural splendor is better viewed from atop the river levee, where the west-facing front façade can be seen in all of its paradoxical glory—permanently inscribed, such as it is, with the words “Pacific Gas & Electric Company,” perhaps to the chagrin of SMUD. The community-owned electrical utility was brought on by Mayor Steinberg in early 2018 during a clutch moment in the $83 million project’s history to help catapult sluggish fundraising to the tune of $7 million and the science center’s 20-year naming rights.

“I see value in understanding your surroundings, visually, when you’re in them,” explains Silva. “By seeing the old building from inside the new one, people understand that the old can be as celebrated and strong as the new.”

While River Station B’s trademark turbines may be long gone (dismantled for parts in 1957 by the property’s then-owner, Sacramento-based Associated Metals Company, no longer in existence), the building is expected to generate electricity in the form of enthusiastic learning and sparks of curiosity. A nebula mural by local artist Jose Di Gregorio emblazons the two-story exhibition hall’s main portal, a stellar welcome for visitors and a foreshadowing of what’s in store as you go deeper into the structure.

At any given minute in Nature Detectives, you may see the kinder contingent and their pet adults imitating animal movements in slow motion, mixing their own audio track using sounds from nature, or digging for insects in a simulated forest floor. “We want them to look at nature with a scientific eye,” says exhibit designer Steve Wiersema. “Look at things up close, at a slower speed, with a much greater eye for detail.”

MOSAC’s main entrance is a siren-red architectural “gasket” that connects the new buildings with the historic structure. (Photo by Kyle Jeffers)

You might wonder what a non-working prototype of the Explorer, the world’s first full-body PET scanner, 15 years in the making, is doing in the museum’s as-yet-unnamed health and wellness gallery, but its co-creator, UC Davis professor of biomedical engineering and radiology Dr. Simon Cherry, is confident that the high-tech contraption will find a rapt audience at the museum, even once kids see beyond its merit as a would-be secret hideout. “Showing kids how blood moves around the body is something explained in textbooks,” says Cherry. “But with this scanner, we’ve been able to create a video for the museum where you can see it go into the lungs and back out to the heart, and get pumped all around the body.” Bodily fluids—the ace up any science center’s sleeve.

On the second floor of the exhibition hall, a makers’ space will stock all the parts and equipment needed to engineer, say, a matchbox-size derby car. “This space is more loose parts,” says Jennifer Martin, MOSAC’s director of experiences, who developed similar labs at science museums in Canada, like the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto and the Telus Spark Science Centre in Calgary. “Sometimes we want experiences that are more loose and open and uncertain. That is a whole other level of learning. For most of us, cold facts and figures aren’t going to trigger curiosity. People like to be engaged in surprising, shocking and funny ways.”

So when you see a kid strapped into a harness and tethered by a bungee cord at the Destination Space exhibit, bouncing along like they are trying to walk on the surface of Mars, looking a lot like Matt Damon’s character in The Martian making his way through a dangerous debris storm to a rocket ship that’s about to abscond to safety without him, you will likely be, as Martin predicts, surprised, shocked and presumably amused.

Designed by Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Jeff Kennedy Associates, the exhibition—which sets a space scene with murals of the moon made from actual Apollo-era photography, plus a movie screen that shows looped film of Rancho Cordova-based Aerojet Rocketdyne test-firing engines—is focused on “the human exploration of space, which does not preclude sending robots to Mars, because that’s all part of the grander plan,” says Kennedy, who has designed space exhibits for the Adler Planetarium in Chicago and the Connecticut Science Center.

Clad in zinc tiles, the planetarium’s exposed dome will gain a splotchy patina that may resemble the surface of the moon. (Photo by Raoul Ortega)

Some of the hands-on displays in Destination Space include powering up a space station using energy from the sun, participating in a launch-a-rocket-ship challenge, and flying a mini drone helicopter in a Mars-like atmospheric vacuum—a scaled-down version of an actual NASA experiment. Apparently Rovers, those robots we’ve already landed on Mars, aren’t the nimble explorers and data collectors that space scientists hope drones will be, and MOSAC is as good a place as any to train future pilots. “We need more things in this city that become part of a child’s memory and experience,” says Mayor Steinberg.

Fair warning—just as astronauts experience the forces of reentry as their spacecraft hurtles toward the earth, so too can you expect some degree of shock once you step out of the cocooning darkness of Destination Space or even the planetarium. Reality will rudely seek to reestablish itself once your eyes start dilating in response to broad daylight, or when you hear a big rig on the freeway sound its blaring horn. But the architecture’s signature flourish—vectors etched into the concrete façade of the new building—offers another chance to be curious before the real world tightens its grasp.

Where will these straight lines—splayed in different directions—connect us to on their way into infinity, Silva asks? For example, which axis points to the River City’s other iconic dome, the State Capitol? Which is aimed at a Google Earth satellite—there are dozens currently in orbit—that has snapped an aerial photo of the new science center? While you’re at it, take a moonshot: Which of these beams will lead to the coordinates of a future space station that you’ll inhabit one day?

Ultimately, the concept of connectivity is about much more than a series of architectural embellishments. As Silva explained earlier, the notion of emphasizing connections in the new museum was rooted in the structure’s original purpose as a power hub—a modern marvel when it was built, powering Sacramento lights, streetcars and more. Back then, River Station B bonded the community. “We saw as the height of technology—the newfound connectivity that brought people together at the beginning of the 20th century,” muses the architect. “Now, here we are at the beginning of the 21st century, with knowledge and information sharing, which is reflected in the mission of a science center.”

Just as the structure has been adapted to connect us once again to our community, it’s also given us a line on the rest of the world and beyond.

Now if someone could just point me in the direction of the Big Dipper….