5 Questions with Amy

Shawn Barba

July 9, 2020

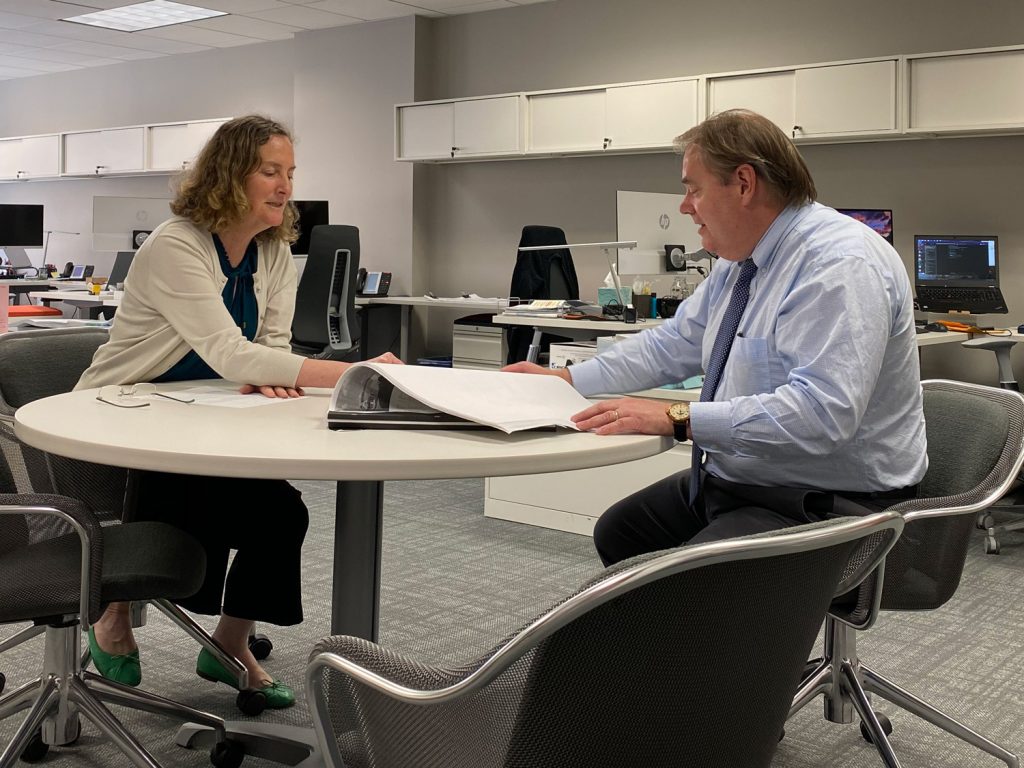

Amy Eliot joined Dreyfuss + Blackford as a Design Principal in December of last year. She brings over 25 years of experience in the Bay Area with a particular focus on Education and Institutional/Public Sector markets and clients. As a licensed architect and LEED professional Amy is a past founding principal of DE+ architecture and has also taught as an Adjunct Associate Professor at California College of the Arts, Department of Architecture and Interior Architecture.

Amy has a passion for civic engagement and community building. She believes that design and design thinking can be primary advocacy tools in the service of social justice, environmental sustainability and strategic development. We are so very excited to have Amy on the D+B team and equally excited to ask her a few questions.

SB: Who has influenced you most when it comes to how you approach your work?

This question is one that many of us are asked and what strikes me is how differently I would answer it over the course of my career, and my life in general. Coming out of graduate school, I was equipped with a great education in a very traditional way, but now looking back to that time from our present day, I realize that ultimately my real education and the most meaningful influencers in my career have often been my peers and clients, significantly more diverse and individually powerful than my design critics in school, (it was the early 1980’s…and there were very few great female role models in that context).

The qualities that connect all my mentors are twofold: a commitment to a high level of ethical responsibility relative to their clients and their communities, and the willingness and ability to speak and act on that commitment, coupled with a dedication to craft in both the evolution of design ideas and their execution. Jim Polshek, of The Polshek Partnership, now Ennead Architects, is someone who has had a long-term impact on how I approach my work for all those reasons. Mario Campi, one of my design critics from the Ticino in Switzerland, taught our entire studio that a dedication to design excellence should never get in the way of a life well lived. And lastly, Billie Tsien (of Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects), who demonstrated to me and many others through our mutual project, the East Asian Library at UC Berkeley, that often the quiet voice has the greatest power to move people.

Those who have influenced me most have been people who implicitly understood me, and yet pushed me often quite hard to take on greater risk as a designer and as a person. I respond well to those types of tactics as I really thrive on challenge, and in some cases, tough love! Our very own John Webre was one of the people who coaxed me out of being terrified about giving public presentations (in that case to the Sacramento City Council for our mutual project, the renovation of the Sacramento Memorial Auditorium), sage advice that I carry with me to this very day.

SB: What are three things you’d like to leave as your legacy?

I was first asked this about 25 years ago around a dinner table (late in the evening after copious quantities of insanely good food and excellent wine), and each person got a chance to respond. The company was diverse and included the CEO of Patagonia, and other equally impressive folks with very personal reflections on this simple but incredibly loaded question. My answer was as follows: Three good buildings that stand the test of time – I think I have one in the bucket so far, which is the Theater at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts.

The many students that I have taught over the years and the hope that my mentorship helped propel them in life and practicing whatever aspect or interpretation of design is meaningful to them and about which they are passionate (I was doing a lot of teaching at the California College of the Arts then and now).

Shifting to today’s context, number three would be my daughter, Hannah. Her perspective has encouraged my advocacy for ensuring that our profession welcomes and embraces, as well as actively supports women and people of color, something that has been an impediment to our profession’s cultural relevance for way too long.

SB: What led you to this career?

Despite my mother mentioning my talent with wood blocks as a toddler, initially my attraction to becoming an architect was because I liked to draw, and the fact that my best friend’s dad had his own practice across the street from our house. I attended a local Waldorf school in Rockland County, NY and as we made our own textbooks for all our classes, I drew constantly. Aside from the other culturally driven assumption that you had to be good at math and science to be a good architect, (I consider myself middling in those departments), I think my teachers and our curriculum encouraged the idea that architecture combined “making” with a holistic and synthetic understanding of the world, and the imperative to drive positive change.

In all seriousness, aside from drawing, what really motivated me to become an architect ultimately was the complexity and infinite variety of what we do as designers, coupled with the cultural and societal responsibility that it entails, and it is this last aspect which captures my passion these days. I see my trajectory in practice as continuing to pursue a broad interpretation of how one can practice design and design thinking in ways that impact our community. These are a few of the reasons I chose to join Dreyfuss + Blackford, in addition to its supportive culture, modernist heritage and 70-year commitment to full engagement with the firm’s practice partners and clients.

SB: What’s one thing you’re currently trying to make a habit?

Active listening….and not always bending toward the analytical mindset. My daughter is my best teacher!

SB: If you could snap your fingers and become an expert in something, what would it be?

Would that it would be that easy, but my secret dream has always been to be a singer able to stand up and belt out a great ballad or blues song. That and being able to make a perfect Tarte Tatin, which unfortunately I did not learn when I was an eighteen-year-old au-pair in France.